What is wrong with the object paradigm ?

17 Feb 2017Disclaimer: Aside from the catchy title, the main point of this article is to asks questions about the weakness of OOP and how some languages provided some element of improvement, by taking a slightly different point of view.

The object paradigm is fundamentally wrong1

If you are curious about programming languages and diverse paradigms, you probably heard or read this sentence more than once. Through those lines, I’ll try to draw a picture of the main reason that can lead peoples to this conclusion. What are the good side and wrong side of OOP, and how we can improve this paradigm by tuning it a little bit. This nice “tunning” is actually already part of some languages, and I’ll refer to it as the ‘category paradigm’.

Where does the object paradigm comes from?

First, let’s recall how, historically, we came to the object paradigm. We are in the late 70s. The C language is now famous as it completely changed the way to write code compared to assembly, is human readable and have a monstrous expressivity in only few language words and the procedural paradigm2 (the one you use while writing C) is well understood. But, as applications grow and get an increasing size, developers are facing an increasingly common problem: the code’s complexity is growing exponentially, and code gets harder and harder to write (it still sounds like a today’s problem, right? :-) ). The object paradigm was developed, expecting to solve the complexity curse. Here came OBJC and C++, both in 1983.

Sadly, we know today that OOP wasn’t the Holly Graal. But what did made peoples believe that it would be, and why is OOP still used today?

The hopes of OOP

What came out from a lot of procedural development is that you often have types that describe some complex structure (for example, linked lists in C are built of chained cells, each cell composed of a value and a link to the next cell) and functions operating on this type (using the same example, function for initialising empty list, destroying list, inserting into this list and removing value from it, etc.). Once you have spotted this coding pattern, it sounds reasonable to formalise it so that you don’t always have to rewrite it by hand, each time. Indeed, this is the best way to involve : spot a pattern that people do mechanically, and automatise it. It worked in the automobile industry, and it also did for computer development. Automatization, from shell script… to new programming languages.

Genesis of OOP

This was the genese of the object paradigm. We call a such data type an object, add an initialisation procedure always called at initialisation, and an other one always called when the resource become unreachable. Namely, OOP’s constructor and destructors. Because we always have lots of methods related to this object that always need as argument this object, we add them to the type definition and call them methods.

Here is an example of the C object pattern :

struct object_type {

int value1;

int value2;

char* ptr;

};

void initialize_object(struct object_type* obj) {

obj->value1 = 7;

obj->value2 = 3;

obj->ptr = calloc(42, sizeof(char));

};

void release_object(struct object_type* obj) {

free(obj->ptr);

}

int do_stuff(struct object_type* obj, int input) {

obj->value1 += input;

obj->value2 += 2;

return obj->value1 + obj->value2;

};

//...

struct object_type obj;

{

initialize_object(&obj);

do_stuff(&obj, 5);

release_object(&obj);

}

And the same thing now in C++:

class Object {

public:

Object();

~Object();

int do_stuff(int input);

private:

int value1;

int value2;

char* ptr;

};

Object::Object()

:value1(7), value2(3) {

ptr = calloc(42, sizeof(char));

};

Object::~Object() {

free(obj->ptr);

}

int Object::do_stuff(int input) {

value1 += input;

value2 += 2;

return value1 + value2;

};

//...

{

Object obj;

obj.do_stuff(5);

}

This example is quite simple, and show how object paradigm is applied both in C and C++ languages. The second language is a lot more error-proof thanks to the support of the paradigm in the language.

Now you might interupt me and argue ‘object paradim isn’t just about methods glued to a type’. And you would be right. I swept under the rug inheritence. This feature actually comes from spotting another codding patter C developers were also doing quite frequently. You reproduce the inheritence by agregating types, and using pointer arithmetic, as shown below.

struct A {

int u;

};

struct B {

struct A parent;

int v;

};

struct C {

struct A parent;

int w;

};

struct B obj_b;

struct C obj_c;

// Upcasting

struct A* p = (void*)&obj_b.parent;

struct A* q = (void*)&obj_c.parent;

The same code in C++ would be:

// In C++, the struct keyword is like the class keyword,

// but all elements are by default public.

struct A {

int u;

};

struct B : public A {

int v;

};

struct C : public A {

int w;

};

B obj_b;

C obj_c;

// Upcasting

A* p = &obj_b;

A* q = &obj_c;

Introducing this feature in the language ensure automatic conversion from B* to A* with the right pointer arithmetic. It remove the risk of often hard to spot bugs. Inheriting doesn’t apply only to type, it apply to methods. You can call methods working with a type A on instance of type B. This is the key reason of this pointer conversion.

The languages C++ and Java alow something even stronguer than reusing methode for subtypes in inheritence hierarchy. Through abstract methods, or Java’s interface, you can force the existence of methods on a given type. Such that the behavior can be different with different types, but the interface to work on them remind the same. Allowing huge code factorisation and genericity of algorithms.

So why is OOP wrong?

Before saying anything, I want to show you how does object looks like in different mainstream languages.

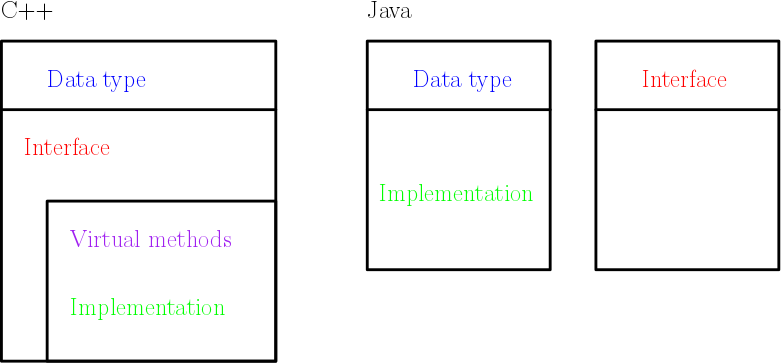

Of course, you can make schemes similar to java in C++ ; interface are obtained through abstract class. It’s just that the language doesn’t prevent you from gluing too many things together (but that’s actually part of the C++ philosophy : allow doing as much thing as you can imagine, but you have to make carefully your design decisions).

Looking at the scheme, we see that always, in both languages, type definition and method definitions are glued together. You can not define a type and later, in a completely independent way, implement methods for this type. Actually, if C++ and Java are the only object languages you have heard about, my last sentence might sounds really strange for you (even maybe sounds like nonsense). But notice that in D, you can implement something rely similar to methods in a complementary independent way of type definition. Why would you do that? Let me give you a tasty example.

A guy (let call him A) make a colorful library describing tasty chocolate biscuits. Here is a little bit of his library.

Biscuit -> Cookie -> FullChocolateCookie

-> WhiteAndBlackCookie

-> Oreo

He think a lot about cooking such wonderful wonders, an implement many sophisticated methods.

Now another guy (named B) just discovered the best way to eat biscuits, so that you can really enjoy all the taste and perfume they carry. Not only for chocolate biscuits, but for any biscuit in the world. He implements many new biscuit, and their eat method. But in those languages, his only way to add an eat method to A’s cookies is to either:

- Re-implement all the biscuit A did in his library, or modify A’s library to add his eat method,

- Encapsulate the A library in some container, like a ‘biscuit metal box’, which is definitively not as easy to eat (especially because metal tends to be harder your teeth).

If you develop library and re-use existing libraries, that’s a problem you probably already encountered many times.

This is because there is actually no good reason to enforce (Java style) interface implementation where type definition occurs. This is the first big issue coming from the way object model is implemented and conceived in developer’s mind.

The second big issue, related to the way OOP is done today, is the huge verbosity and boilerplate code introduced by encapsulation. Good books like ‘effective C++’3 even recommend doing so. You see it everyday, from getters and setters mostly doing one-line affectation (many ide have tools for automating this code generation) to constructor only forwarding argument to member variables. I really like the following example from LLVM’s documentation:

AST Bidule {

ASTBidule(t1 a, t2 b, t3 c)

:a(a), b(b), c(c) {};

t1 a;

t2 b;

t3 c;

};

So much redundancy. Have a look at LLVM’s example for heavily verbose C++ code (that is actually good C++ practice…). Each variable’s name is written three times. I would say that this code is three times longer that it should be (I mean, if we was living in a perfect world). But there isn’t a better way to do it, conforming to usual understanding of OOP. If so, LLVM’s developer would have found it and spreed the word.

The categoric paradigm

What I call categoric paradigm is a way of doing OOP in some functional languages like Haskell, but also Rust. Up to a certain amount it can also be done in D.

The main idea is that types remain types (aggregated data), functions and procedure remain procedures. Sets of procedures can be regrouped together in a typeclass definition. A typeclass (it’s a mathematical class) definition is similar to a java interface. Types that become instances of this typeclass should implement its methods, but the main difference is that the belonging of a type T to a given typeclass C can be stated independently of the typeclass definition and of the type definition. In rust, typeclass are named trait. Types are types (as they are in C) and the link between them, the instanciation of the trait of a type can be done independently of the definition of the trait and of the definition of the type.

Here is bellow a short example from rust’s documentation4:

// # A Sheep object:

struct Sheep { naked: bool, name: &'static str }

impl Sheep {

fn is_naked(&self) -> bool {

self.naked

}

fn shear(&mut self) {

if self.is_naked() {

// Implementor methods can use the implementor's trait methods.

println!("{} is already naked...", self.name());

} else {

println!("{} gets a haircut!", self.name);

self.naked = true;

}

}

}

// # The Animal typeclass/trait/interface:

trait Animal {

// Static method signature; `Self` refers to the implementor type.

fn new(name: &'static str) -> Self;

// Instance method signatures; these will return a string.

fn name(&self) -> &'static str;

fn noise(&self) -> &'static str;

// Traits can provide default method definitions.

fn talk(&self) {

println!("{} says {}", self.name(), self.noise());

}

}

// # The implementation of the `Animal` trait for the type `Sheep`.

impl Animal for Sheep {

// `Self` is the implementor type: `Sheep`.

fn new(name: &'static str) -> Sheep {

Sheep { name: name, naked: false }

}

fn name(&self) -> &'static str {

self.name

}

fn noise(&self) -> &'static str {

if self.is_naked() {

"baaaaah?"

} else {

"baaaaah!"

}

}

// Default trait methods can be overridden.

fn talk(&self) {

// For example, we can add some quiet contemplation.

println!("{} pauses briefly... {}", self.name, self.noise());

}

}

See how this three things can be done independently.

Similar things can be archived in haskell, though constructor and destructor doesn’t exist. But Haskell’s variable are by default immutable, and the language is full of laziness. In a such context, looking for a constructor or a destructor doesn’t make sens. But for the curious, what is done in rust for methods can be done in the same way in Haskell.

Conclusion

Though this article have a really catchy title, the main point is to show you another perspective for the concept of object that is quite different from the one OOP’s developer are used to. The first goal is to show the weakness of the object paradigm, and the second is to demonstrate how some of them can be strengthen from a small switch in the viewpoint, using emerging languages for examples. The view point demonstrated here is more known in the functional programming land (although not all functional programming languages offers such features). The Mozilla fondation made a wonderful work by creating rust, a language that provide both the functional and procedural paradigms, and also allow taking the object approach in cases where it fits better than the two previous paradigms. I hope that it made you question yourself on the object oriented paradigm and developed your curiosity for other languages. The other languages mentioned are not mainstream, but the ideas they carry appear increasingly in many languages and if we cannot say which language will be the language of tomorrow, we can be sure that this language will provide many tools that are common in the functional world, probably together with our usual tools from procedural languages. So don’t turn your head away, just because your favorite language doesn’t provide such features :)

-

Things aren’t black and white. The object paradigm is definitively well suited for many tasks like modeling GUI. ↩

-

Procedural paradigm means essentially that the language provide functions with side effects, and code is written linearly. You can see it like an enhencement of languages that only provide goto and jumps. ↩

-

This is a really good book on good programming advices for C++ developer. Despite the critic made in this article, it’s definitively a book full of good practices. ↩

-

See rust traits ↩